| New

Market- Woodstock

MM 266

This point provides one of the best views along 81 of New Market Gap, visible as a notch in the Massanutten Synclorium behind the town of New Market. Route 211 travels through this notch, and it might seem reasonable to suppose that humans made the cut to accommodate the traveling needs of the town. Humans are only a moment, though, in the history of histories and a closer

look at the formation of New Market Gap should reveal a secret or two about Nature's own dynamite.

Humans are only a moment, though, in the history of histories and a closer

look at the formation of New Market Gap should reveal a secret or two about Nature's own dynamite.

Remember that Massanutten is armored along the upper ridges with resistant Massanutten sandstone, making erosion difficult. This fact makes it unlikely that the notch formed after the mountain did. So imagine, instead, New Market as it was in the Mississipian period, about 350 million years ago. The effects of the Taconic Orogeny had simmered and Virginia rested in a brief (about 40 million years) period of calm, where warm shallow waters hosted an abundance of invertebrate life. This tropical vacation was short-lived, however, and by the end of the Mississippian period, the Alleghanian Orogeny had begun. As the west coast of Africa skidded into the East coast of North America, mountains of Himalayan proportians shuffled through Virginia1.

During that orogenic time, it is likely that some stream or river existed

in the place of present-day New Market Gap. As the mountains thrust to

higher elevations, the stream incised into the rock. That is, the stream

gradient increased, allowing the river to erode more quickly.

In this way, the mountains in present day New Market rose around the stream, leaving a notch. New Market Gap is the product of this long history, visible in the road cuts of that scenic mountain drive.

MM 268

In pastures west of 81, Third Hill rises unmistakable against the flat slopes. Comprised primarily of bedded chert, this hill shows how the relative resistivity of rock types can influence topography. Chert, like other carbonates in the Valley, is a sedimentary rock that forms in marine environments. The origin

of chert remains somewhat of an enigma to geologists, and several theories

exist to explain it. One certainty is that some marine orgainisms extract

silica (SiO2) from the seawater and use it to make opal skeletons. Very

stylish. When these organisms die, the skeletons drift to the sea floor

and dissolve. Only about one percent of the opal produced by these creatures makes the stratigraphic record, but after a few million years of accumulation, the opal crystallizes to chert. Most of the world's major deposits of bedded cherts are associated with deep water deposition near continental margins. Some geologists speculate, however, that chert can form in shallow environments1.

In pastures west of 81, Third Hill rises unmistakable against the flat slopes. Comprised primarily of bedded chert, this hill shows how the relative resistivity of rock types can influence topography. Chert, like other carbonates in the Valley, is a sedimentary rock that forms in marine environments. The origin

of chert remains somewhat of an enigma to geologists, and several theories

exist to explain it. One certainty is that some marine orgainisms extract

silica (SiO2) from the seawater and use it to make opal skeletons. Very

stylish. When these organisms die, the skeletons drift to the sea floor

and dissolve. Only about one percent of the opal produced by these creatures makes the stratigraphic record, but after a few million years of accumulation, the opal crystallizes to chert. Most of the world's major deposits of bedded cherts are associated with deep water deposition near continental margins. Some geologists speculate, however, that chert can form in shallow environments1.

MM 269.2

Although the Shenandoah River is no novelty to anyone living in the Valley, many people might be surprised to learn how fluvial processes allow the river to traverse across the Valley, making and unmaking the land on which we live.

Understanding these processes would be made simple with two tools- a plane and a snorkel. Although this tour provides neither, some of the accompanying photographs and diagrams should suffice.

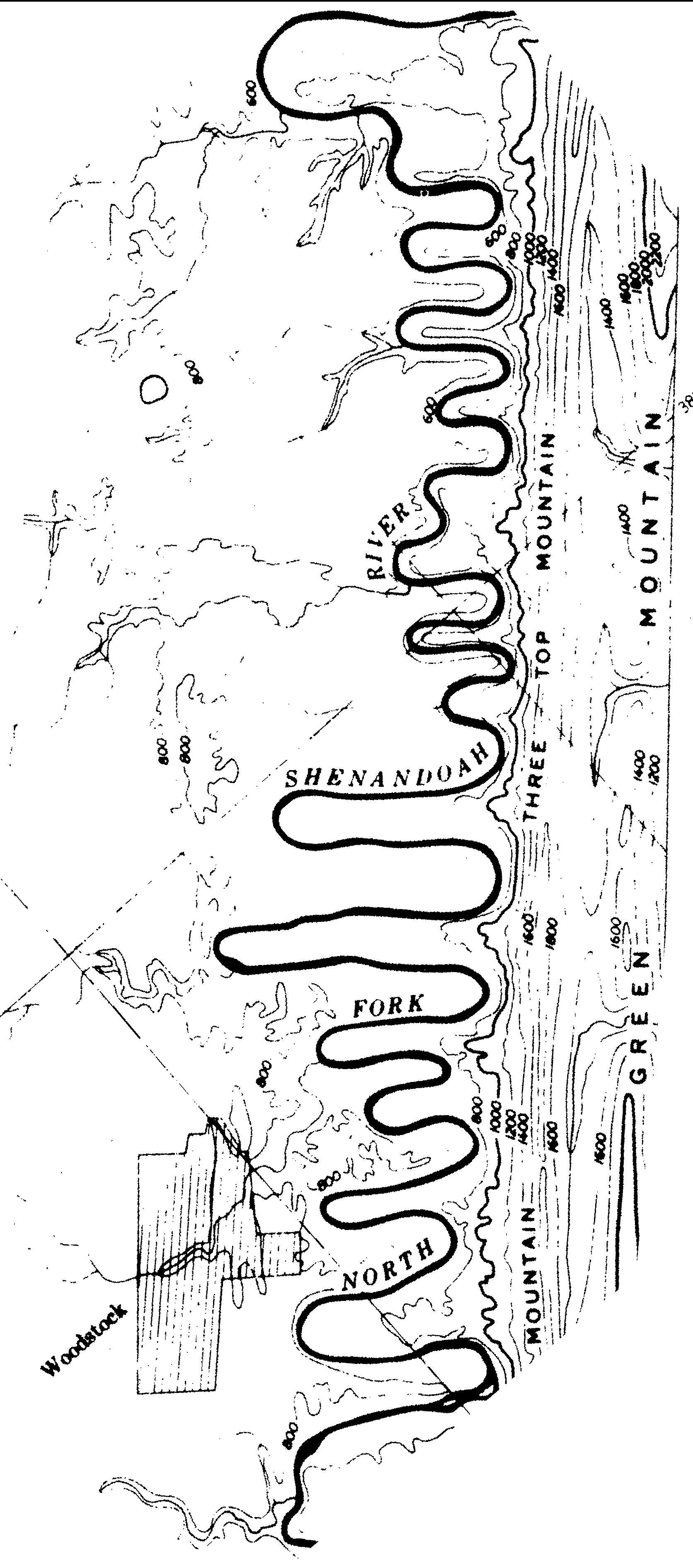

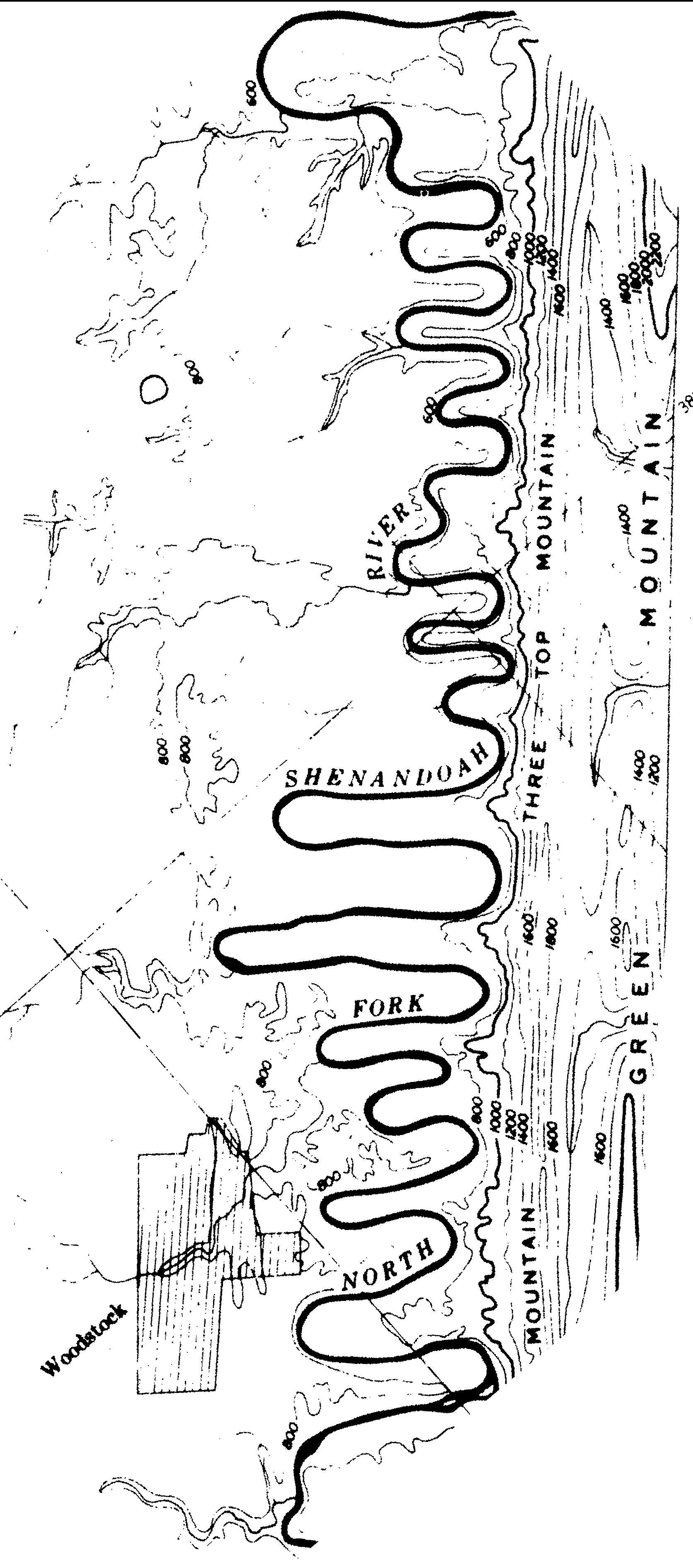

| An arial view 1

of the Shenandoah River shows several geologic features. Most prominent from this panorama is the snakelike, or meandering, channel pattern that is characteristic of mature streams. Mature streams develop in areas of minimal elevation change and possess very low gradients. |

|

As gravity becomes less helpful in

moving water quickly, mature rivers lose their ability both to carry large

loads and to incise

into the strata below them. Because these rivers do not have the

strength to plow direct and straight through the soil and rock opposing

them, they begin to search more vigorously for easier paths through which

to maneuver. Rounded S channel patterns develop. Click here for a cross-sectional

illustration of this meandering process.

Shown above are the seven bends of the Shenandoah,

located near 81 North of New Market and visible from Lookout Mountain.

This section of the Shenandoah examples this practice of traveling along

paths of least resistance. Here the Shenandoah Valley floor is jointed,

so that the underlying rock structure is cross-hatched. When the Shenandoah

River, traveling from south to north, encounters these joints, it changes

course and follows them east- west. Eventually it reaches a more resistant

rock type and turns north again. When it reaches another joint the pattern

repeats itself. Between Edinburg and Strasburg the meandering course of

the Shenandoah River is over fifty miles long, while the straight line

distance is only about fifteen miles.

275

East of this stretch of highway is Short Mountain, whose proximal slopes bear several grey patches void of foliage. These are block fields, preserved landmarks from the last Ice Age1.

Beginning in the Pleistocene Epoch

about two million years ago (mya) and ending only ten thousand years ago,

the last Ice Age carried one mile thick ice sheets to the nothern reaches

of present day North America. Although the glaciers never reached Virginia,

cold climates did penetrate this far south. Treeline dipped low, exposing

many of the upper mountain slopes. Ground water in the slopes underwent

severe freeze and thaw events. When water in rock freezes it expands and

forces the rock apart. This action creates fields of angular boulders known

as talus.

Talus slopes formed in Virginia above treeline during the Ice Age, and

the unstable rocks tumbled through many avalanches.

Beginning in the Pleistocene Epoch

about two million years ago (mya) and ending only ten thousand years ago,

the last Ice Age carried one mile thick ice sheets to the nothern reaches

of present day North America. Although the glaciers never reached Virginia,

cold climates did penetrate this far south. Treeline dipped low, exposing

many of the upper mountain slopes. Ground water in the slopes underwent

severe freeze and thaw events. When water in rock freezes it expands and

forces the rock apart. This action creates fields of angular boulders known

as talus.

Talus slopes formed in Virginia above treeline during the Ice Age, and

the unstable rocks tumbled through many avalanches.

When a more temperate climate returned to

the South, foliage began to grow again on the barren reaches of upper mountains. Over several thousand years, trees rooted over most of the slopes. Movement in the talus fields made foliage growth difficult, and some bare patches remain. These areas are block fields.

MM 278

| Further south, near Harrisonburg, the Alleghany Mountains are too distant from route 81 to perceive. These mountains, like the Shenandoah Valley, are part of the Valley

and Ridge Province. From this northern vantage, however, the

distance lessens between the Alleghany Mountains and the Blue Ridge Mountains. Consequently, Little North Mountain becomes visible as the ridgeline to the west. Within Little North Mountain are rock beds that provide evidence of some difficult circumstances surrounding the Taconic Orogeny, a mountain building event that occurred about 450- 440 mya. |

| During this time, a large chain of volcanic islands, called the Arvonia/ Chopawansic terrane, collided with eastern North America, which existed as a snorkeling paradise, a very shallow sea teeming with life. Simplistically, oceanic crust (on which the island arc rested) slid underneath the North American continent, thrusting it up into mountains. Behind this building, the craton sank into a deep foreland basin. |

| Complications in this collision arose because

of the jagged shape of the North American coast. Also the collison was

not head- on, but angled from the southeast. Some areas were exposed to

heavy impact and others were more buffered. Northern Virginia and Maryland

were protected and so deformation was mild, resulting more from squeezing

than from impact. While more exposed areas formed mountains similar to

the present day Alps, Northern Virginia swelled into an arch that separated

two depositional basins. Although natural processes since that time

have obliterated the Little North Mountain Arch, its name reveals that

some remnant evidence still exists in outcrops on and around Little North

Mountain, visible in the mountains out your driver's side1. |

MM 281

Just before reaching Woodstock, Edinburg

Gap appears as a notch in the ridgeline to the right. This gap formed by

geologic processes identical to the New Market Gap further south. Mile

marker 266 provides a thorough explanation of the formation processes at New Market Gap. |

Humans are only a moment, though, in the history of histories and a closer

look at the formation of New Market Gap should reveal a secret or two about Nature's own dynamite.

Humans are only a moment, though, in the history of histories and a closer

look at the formation of New Market Gap should reveal a secret or two about Nature's own dynamite.

In pastures west of 81, Third Hill rises unmistakable against the flat slopes. Comprised primarily of bedded chert, this hill shows how the relative resistivity of rock types can influence topography. Chert, like other

In pastures west of 81, Third Hill rises unmistakable against the flat slopes. Comprised primarily of bedded chert, this hill shows how the relative resistivity of rock types can influence topography. Chert, like other

Beginning in the

Beginning in the